In March, a quiet coastal town in the western Indian state of Gujarat could have given both Davos and Coachella a run for their money.

That’s when billionaires and movie stars from around the world jetted to Jamnagar, overwhelming its small airport with private planes and chartered flights. They were all there to party with Asia’s richest man, Mukesh Ambani.

The 67-year old chairman of India’s most valuable private company Reliance Industries had thrown a lavish pre-wedding bash for his son, welcoming around 1,200 guests from Silicon Valley, Bollywood and beyond. Mark Zuckerberg, Bill Gates and Ivanka Trump were among the many high-profile celebrities in attendance.

The three-day celebration, which saw performances by popstar Rihanna and magician David Blaine, transfixed India and further underscored Ambani’s growing global clout.

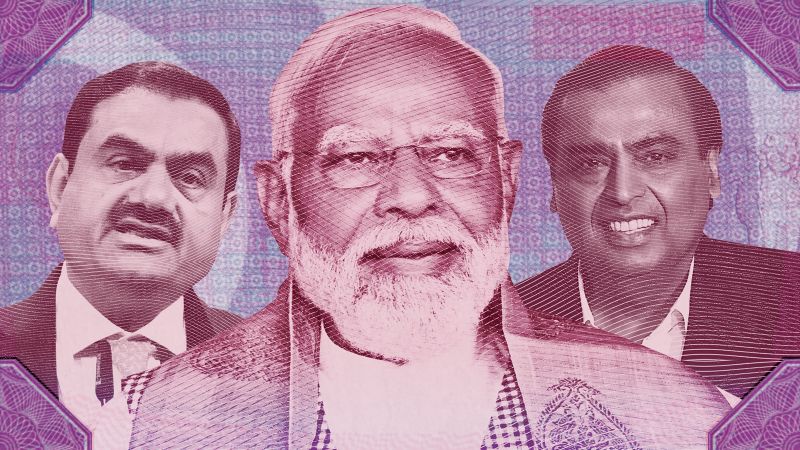

But Ambani was not the only Indian businessman at the bash whose staggering influence and riches are reshaping the world’s most populous country.

Fellow billionaire Gautam Adani, founder of the Adani group, was also invited. The infrastructure tycoon has stunned the world with his supercharged rise in the last decade. In 2022, he briefly ousted Jeff Bezos as the world’s second-wealthiest person.

“They are phenomenal … entrepreneurs, who have been able to sustain steady growth and development in a vibrant yet sometimes chaotic political and business environment that exists in India,” said Rohit Lamba, an economist at Pennsylvania State University.

Investors have been cheering the duo’s ability to adroitly bet on sectors prioritized for development by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, currently campaigning for his third consecutive term to lead India.

The South Asian country is poised to become a 21st-century economic powerhouse, offering a real alternative to China for investors hunting for growth and manufacturers looking to reduce risks in their supply chains.

Reliance Industries and the Adani Group are sprawling conglomerates worth over $200 billion each, with established businesses in sectors ranging from fossil fuels and clean energy to media and technology.

As a result, these three men — Modi, Ambani and Adani — are playing a fundamental role in shaping the economic superpower India will become in the coming decades.

In India’s financial capital Mumbai, the fingerprints of the two businessmen are everywhere, starting from the bustling international airport, which is operated by Adani.

Their names are plastered across the city — from the bubble lettering of the Adani Group logo propped up beside highways to high-rise apartment buildings branded with Adani Realty, to cultural institutions named after the Ambani clan.

Some spaces need no names or bright labels, but their affiliations are just as obvious. Everyone in Mumbai knows who lives in Antilia — the personal skyscraper of Ambani and his family, which reportedly cost $2 billion to build and boasts a spa, three helipads and a 50-seat theater. The 27-story building sits on a street dubbed “Billionaires’ Row,” its jutting geometric architecture looming over the neighborhood.

The kind of power and influence these Indian tycoons enjoy has been seen before in other countries experiencing periods of rapid industrialisation.

Both Ambani and Adani are often compared by journalists to John D Rockefeller, who became America’s first billionaire during the Gilded Age, a 30-year period in the last decades of the 19th century.

During those decades, industrialists saw their fortunes ascend to staggering heights thanks to the rapid expansion of trains, factories and urban centers across America. Other famous names including Frick, Astor, Carnegie, and Vanderbilt also shaped the country’s infrastructure.

More recently in Asia, “chaebols” or giant family-run conglomerates have dominated the South Korean economy for decades and many of them, including Samsung and Hyundai, have become global leaders in semiconductors and autos.

“India is in the middle of something that America and lots of other countries have already gone through. Britain in the 1820s, South Korea in the 1960s and 70s, and you could argue China in the 2000s,” said James Crabtree, the author of The Billionaire Raj, a book about India’s wealthy.

It is “normal” for developing nations to go through such a period of rapid growth, which sees “income accumulation at the very top, rising inequality and lots of crony capitalism,” he added.

The Indian economy has many of those characteristics.

Worth $3.7 trillion in 2023, it is the world’s fifth largest economy, jumping four spots in the rankings during Modi’s decade in office and leapfrogging the United Kingdom.

It is comfortably placed to expand at an annual rate of at least 6% in the coming few years, but analysts say the country should be targeting growth of 8% or more if it wants to become an economic superpower.

Sustained expansion will push India higher up the ranks of the world’s biggest economies, with some observers forecasting the South Asian nation to become number three behind only the US and China by 2027.

Despite these successes, soaring youth unemployment and inequality remain stubbornly persistent problems. In 2022, the country ranked a lowly 147 on gross domestic product (GDP) per person, a measure of living standards, according to the World Bank.

To spur growth, the Modi government has begun a massive infrastructure transformation by spending billions on building roads, ports, airports and railways.

It is also heavily promoting digital connectivity, which can improve both commerce and daily life.

Both Adani and Ambani have become key allies as the country embarks on this revolution.

“These conglomerates are very, very important and very well connected,” said Guido Cozzi, professor of macroeconomics at the University of St Gallen in Switzerland, noting that both the Adani Group and Reliance Industries were founded years before Modi came to power.

“They are not typical stagnant monopolistic conglomerates. They are pretty dynamic,” Cozzi said. Not only are they playing “an important role” in building infrastructure, which helps “growth directly,” the two business groups are also helping the country expand “indirectly” by boosting connectivity through digital innovation, he explained.

Reliance was founded by Ambani’s father, Dhirubhai, as a small yarn trading firm in Mumbai in 1957. Over the next few decades, it grew into a colossal conglomerate spanning energy, petrochemicals and telecommunications.

After his father’s death, and following a bitter feud with his younger brother, Ambani inherited the company’s main oil and petrochemicals assets. He then spent billions transforming it into a tech juggernaut.

In less than a decade, Ambani has not only upended India’s telecom sector, but also become a top player in sectors ranging from media to retail.

His ambition and breathless pace of expansion is matched by Adani, a college drop-out who now helms businesses ranging from ports and power to defense and aerospace.

A first-generation entrepreneur, the 62-year-old began his career with diamond trading, before setting up a commodity trading business in 1988, which later evolved into Adani Enterprises Limited (AEL).

According to a January note by American brokerage firm Cantor Fitzgerald, AEL “is at the core of everything India wants to accomplish.”

The company functions as an incubator for Adani’s businesses. Many have been spun out and become leading players in their respective sectors. According to Cantor, the firm’s current focus on airports, roads and energy make it “a unique long-term investment opportunity.”

And while both the barons built much of their fortune from fossil fuels, they are now investing billions in clean energy. Their green energy pivot comes at a time when India has set itself some ambitious climate goals.

The world’s fastest growing major economy has other conglomerates as well. The 156-year-old Tata Group wields immense power over various key sectors ranging from steel to aviation, but it often does not invite the same scrutiny as the newer conglomerates, mainly because it is controlled by philanthropic trusts and not run as a family dynasty.

Ambani and Adani are considered vocal champions of Modi. Prominent politicians from opposition parties in India have often questioned Modi’s ties with India’s super-rich, and the meteoric rise of Adani becoming a fraught issue last year.

In January 2023, the group was rocked by an unprecedented crisis when an American short-seller Hindenburg Research accused it of engaging in fraud over decades.

Adani denounced Hindenburg’s report as “baseless” and “malicious.” But that failed to halt a stunning stock market meltdown that, at one point, wiped more than $100 billion off the value of its listed companies.

Political leaders from India’s main opposition party ferociously questioned Adani’s relationship with the prime minister, and some even said that they were punished for pursuing the issue.

Since then, Adani has made a remarkable comeback, with shares in some of his companies touching record highs. Despite the scandal, the group has also managed to attract billions from new foreign investors, including US private equity firm GQG Partners.

“While that report brought to light serious concerns, we believe the company has taken actions to reduce liquidity risk, improve governance, and increase transparency,” Cantor said in its report. “Thus, at this juncture, we believe Adani is too big to ignore, and for India, we believe the country needs Adani as much as Adani needs the country.”

Now, as India votes, Modi’s perceived relationship with the billionaires is once again being questioned by rivals.

Prasanna Tantri, associate professor of finance at the Indian School of Business, said he does not have “reason to believe that things have become worse than before” when it comes to crony capitalism in India.

Some processes, particularly more transparency in allocation of India’s natural resources and the overhauling of the country’s bankruptcy laws, have been important reforms under Modi, he added.

Experts say that some amount of closeness between politicians and business elite can help in growing the nation faster.

“The optimal level of corruption in an economy is never zero,” said Crabtree, adding that India needs to build more independent institutions that can keep it under control.

However, unchecked dominance of such enormous groups may choke competition and innovation, and ultimately lead to stagnation in an economy.

The new government needs to encourage entrepreneurship and innovation by making it easier for smaller firms to raise money and getting rid of archaic laws, including land and labor rules, that can get in the way of doing business. Failing to do so, could stifle India’s future growth.

A few big conglomerates cannot absorb the million people joining the labor force every month, said Lamba, who is also co-author of Breaking the Mould, a 2023 book that examines how Asia’s third largest economy can grow faster.

“India cannot grow rich before it becomes old on the back of a few big firms like Adani or Ambani,” he said. “India should make more firms.”

Read the full article here